“A bulletin board at Lakes Community High School. EMILY CODY”

Source: http://www.wsj.com/articles/serial-podcast-catches-fire-1415921853

SPOILER ALERT (re Serial episodes 9-12)

I have recently finished listening to the entire 12 episode podcast series Serial. Up until the penultimate episode, I was a fan. Talking about it water cooler style at work, recommending it at parties when the conversation came up, methodically avoiding articles and online chatter so as to avoid spoilers…that type of fan. Up until the penultimate episode, I was a serial Serial proponent. In fact, even up until the last 8 minutes of the penultimate episode. Even up until the last 3 minutes.

But immediately following the end of that episode, I felt a visceral tightness that didn’t sit right with me. This unexpected feeling, I now realize, was an understanding manifested in the pit of my stomach—that I had been deluding myself the entire time I had been listening to the series.

In the last 8 minutes of the second to last episode, Episode 11 “Rumors,” Sarah Koenig discusses a letter that Adnan Syed wrote to her after she had been talking to him about some of the rumors she was hearing about him. A single spaced, typed eighteen page letter in the mail. Here is the transcript of the parts in which she quotes the letter:

“As I look back now” he wrote, “I realize there was only three things I wanted after I was convicted. To stay close to my family, prove my innocence and to be seen as a person again. Not a monster.” The third one he says he’s managed, inside prison.

“People in here know me as a stand up guy. Guards, inmates, staff, people I’ve been around for fifteen years have seen me every day, recognize me as someone whose word can be trusted. I guess what I’m trying to say is that I was able to find the peace of mind in prison that I lost at my trial…”

“I didn’t want to do anything that could even remotely seem like I was trying to befriend you or curry favour with you. I didn’t want anyone to ever be able to accuse me of trying to ingratiate myself with you or manipulate you…I had a rough year, my step father died in April, then my father died two months later…but I couldn’t say anything to you because I had to stick to what I know. Can you imagine what it’s like to be afraid to show compassion to someone out of fear they won’t believe you? I was so ashamed of that…”

“I’m always overthinking. Analyzing what I say, how it sounds and the fact that people always think I’m lying. All this thinking, it’s to protect myself from being hurt. Not from being accused of Hae’s murder, but from being accused of being manipulative or lying. And I know it’s crazy, I know I’m paranoid, but I can never shake it because no matter what I do, or how careful I am, it always comes back. I guess the only thing I could ask you to do is, if none of this makes any sense to you, just read it again. Except this time, please imagine that I really am innocent. And then maybe it’ll make sense to you.”

At this point he wrote, “It doesn’t matter to me how your story portrays me, guilty or innocent. I just want it to be over.”

Right now as a listener, I myself am feeling ashamed. I am feeling deep discomfort at the way in which I and over 5 million others have played detective, devoured as entertainment this podcast that systematically wrenches apart the “peace of mind” many people have worked hard to create. Not just Adnan, but Hae’s family and friends and the countless other loved ones who have been pained and affected by this murder over the last fifteen years.

This shame that I am feeling from hearing Adnan’s letter I expect to hear mirrored in Koenig’s analysis of it. I keep listening:

At this point he wrote, “It doesn’t matter to me how your story portrays me, guilty or innocent. I just want it to be over.”

It will be. Next time. Final episode of Serial.

With those 9 words she ends the episode and with it goes much of my respect for her and for the show in general. What I expected to be a moment of sobering self-reflection instead became a tool for keeping up the drama, keeping the audience engaged with a teaser for the last episode. Hungrily prioritizing the arc of the podcast at the expense of the human lives at stake, right when Adnan calls her out for essentially doing just that.

I had looked past this tendency of Sarah Koenig’s for nearly the entire season, inexcusably because I was riveted. And I thought it was ok to be riveted, to listen at the edge of my seat as if this real murder case was another episode of Law and Order. Maybe because it was under the guise of journalism, so it made me feel like listening was a viably intellectual endeavor. Or maybe because I thought it was properly critical of the fallacies of the criminal justice system. Or maybe because I liked how “real” Sarah Koenig seemed—that she inserted her wavering subjectivity where other reporters have feigned objectivity.

All of these delusions were broken when I heard the 9 words she chose to close Episode 11.

Sarah Koenig

Source: http://www.dailycal.org/2014/10/10/serial-podcast/

Even in her lead-up to Adnan’s heartbreaking letter, Koenig reveals more of this type of dehumanizing and minimizing language.

She says that Adnan gave his “reluctant permission” to talk about the letter. His reluctance should have been telling to her, that it was perhaps too personal or that he suspected his words would be, in an ironic twist, ripped apart as has come true. We get none of this backstory; we don’t hear how she convinced him to get past that reluctance because the important thing is that he did, in the end, permit her to talk about the letter, so she can and will and did.

She then introuces the content of the letter by saying, “It’s a good letter, he’s a good writer, but it swung from pole to pole, from distrust to gratitude to confusion.” I’m sorry but did we suddenly enter a 10th grade English classroom? Where do you get off making a judgment on the quality of the writing of a heartfelt disclosure? Hmm, it’s a “good letter” but it’s a bit unfocused so C+, Adnan. Regardless of what you think of his innocence or lackthereof, if that were someone’s reaction to my finally laying bare what I have been afraid to say to them for a year, about my mixed emotions and complex misgivings, about my having to process the death of two parents while said someone rips apart my life and accuses me of murder, manipulation, sociopathy, and meanwhile tells me I’m a “nice guy”…well, really, I don’t know what I’d do, but I don’t think it would be pretty.

At the end of this introduction, before she reads the quotes from the letter, she says, “I could tell that my story had messed with his equilibrium.”

There is more truth to that understatement than I think Koenig even realized, simply in the perhaps unintended word choice of “my story.” What it comes down to is that this podcast really is just a story for Koenig, and one in which centers herself.

This sentiment is reflected in an interview in Vulture. She discusses how she came up with the idea for Serial:

“I remember driving back to New York from Asheville, North Carolina, and listening to many books on tape, and it hit me that those were the audio stories I liked the best — sustained narratives that you can lose yourself in for not just minutes, but hours and hours. And I thought, Why don’t I just try to create a show that replicates the experience of a book on tape?

So you think of “Serial” as a radio book? Your own true-crime potboiler paperback?

Well, I’m not probably supposed to talk about it in those terms, but even though I have never written a book before, this to me feels like it must be close to that process. The only difference is if I was writing a book, I would do all the reporting first and then organize it like a normal person and then publish it, but here, I am releasing my work as I go, which is sort of crazy, I realize.

Speaking of potboilers, do you think of yourself as a detective when you narrate this piece? I sense a bit of that vibe coming from you.

Well, it does help me when I sit down at the mike to kind of think of myself as a character and put that hat on. I just took my daughter to see Double Indemnity, the noir-iest noir there is, and I thought, Am I that detective right now?…”

This is the key, the genesis of nearly all the ethical problems people have with Serial. Sarah Koenig set out to emulate fictional audiobooks, and she conceptualizes Serial at least partially in that way.

She understands that this is not what she is “supposed” to say and feel. On some level this means she knows her thinking is problematic. I wonder though, if she realizes why exactly. No wonder she has such a huge fanbase. No wonder consumers like myself get lost in the narrative in the same way they would a television crime drama or mystery novel, as many critics have pointed out. It is because that is what the show was modeled after. It was designed to hook listeners so that they “lose [themelves]” in the story. It had little to do with Hae or Adnan or the specific people in this case, which is why their actual current lives are often incidental compared to Koenig’s protagonist/conflicted detective “character.”

Once I felt this unease and shame after Episode 11, things that I had seen as merely bothersome I now saw in a new light. Koenig’s manner of questioning, for example. Or should I say her aching see-saw vocal tone that’s, like, not quite so…confident? You know what I mean? Or—I mean…right?

Image from a hilarious and eerily real parody from Funny or Die

Source: http://mashable.com/2014/12/17/serial-parody-sarah-koenig/

Sometimes when listening to her I feel like I’m listening to a parody. But it’s all for a purpose—so that listeners and interview subjects alike see her as relatable, as a friend, as someone who is just like them in terms of confusion, uncertainty, at times exasperation. It’s a tactic, and it’s one that can be very effective. Just look at her response to another question in her Vulture interview:

“Yes, I could say, there was a point where I thought I knew the truth,” she says. “And then I found out that I didn’t know as much as I thought I did, and I did more reporting, and now I don’t know what I don’t know again! Are you mad at me? Don’t be mad at me!”

The important thing about this tone, this insecure, see-saw “I’m-just-like-you” tone, is that it allows her to speculate all over the place, about everything, on every side of the spectrum, but cover herself as a reporter and likeable narrator by writing it off with a simple “but I mean…I don’t know.” This is the same tactic that allows her to assume both the “savior” and “executioner” role that Adnan mentions in Episode 11, speculatively praising him and maligning his character, often in one breath. (The psychological toll that this savior/executioner dichotomy must take on Adnan is part of what you see coming out in his letter).

There’s a stellar piece by Jessica Goldstein on ThinkProgress that breaks down some of the ethical questions of Serial one by one. In it, Edward Wasserman, Dean of the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, says that Serial provides a “totally riveting experience,” but he speaks to the “collateral harm” in leaving dangling questions about a person’s character:

“It’s not a complete defense to say, ‘I’m just raising these as hypotheticals; I’m not saying it’s true.’ Because raising a hypothetical that [someone] is a lying sack of shit, and making it public, it’s leaving a question out there that may turn out to be groundless. That is a valid concern…”

“Gratuitous defamation is something that should be avoided,” he said. “And it’s unavoidable when the reporter is thinking out loud en route to that conclusion.”

Koenig broke a precedent of reporting by showing all her work and airing it publicly like a math problem she’s in the middle solving. Inherently, this is exciting for an audience. But what is the cost to the people involved in the case? We’re not just talking about Adnan here. Koenig defames and questions the integrity of pretty much everyone involved at one point, from Jay to the jurors to Jenn to Kathy to Kevin Urick to Christina Gutierrez to Detectives Ritz and MacGillivary to Mr. S…nerarly everyone interviewed and/or affected by this murder.

Jay is one of the ones that gets it the worst, this hypothetical defamation that’s put out there on the table and left there like a bowl of rotting fruit. Koenig’s distrust of Jay’s testimony and his shifting stories leads to implications of deeper questions of his character, which build and fester despite never pointedly being stated as fact. It is clear from his three part interview in The Intercept that he felt dehumanized by Koenig’s version of events, saying that he felt like Koenig created an “evil archetype” of him. Snippets from two distinct email responses to him show her defense:

“Please know that, to me, this case has never been an entertainment. I am mindful all the time that everyone involved in this case is a real person – not an archetype, not a character, not a stereotype – but a real person. I don’t know if you’ve listened to the podcast, but in every episode I tried to convey that, and to respect that…”

“My intention has been the same from the beginning: To get the story right, and to treat everyone fairly. There are so, so many things I could have reported, but didn’t, because they seemed potentially damaging or unfair, and they weren’t directly related to the crime. Not just about you, but about other people involved in the case. In other words, I’m not out to get anyone, or to damage anyone’s reputation. I only reported information that we deemed relevant to understanding the case.”

To me, these responses demonstrate that Koenig doesn’t understand the idiom about the road to hell being paved with good intentions. Perhaps to you this case has never been entertainment and perhaps you are mindful all the time that the people involved are real people, but Koenig—how are you telling the story to your audience? Through cliffhangers, teasers, and catchy dramatic music. That’s entertainment. Why were I, and some other listeners suddenly reminded that this story is about real people only when we heard Adnan’s letter in the second to last episode? How were you crafting this story in a way that made us forget in the first place?

Jay Wilds

Source: Natasha Vargas-Cooper

https://firstlook.org/theintercept/2014/12/29/exclusive-interview-jay-wilds-star-witness-adnan-syed-serial-case-pt-1/

Jay’s Intercept interview gave me another dose of that “these are real people” realization in the pit of my stomach. He talks about losing a construction job three weeks into the podcast, and about how he no longer lets his children walk to school because, since the podcast aired, Serial listeners from Reddit have found where he lives and videotaped him and his home. He talks about fearing worse for his wife and his kids’ safety.

He also mentions what some of the other people who knew Hae and Adnan were thinking and feeling when Koenig started going around asking questions:

When I was [in Baltimore], I heard from a few people that [Koenig] was harassing people at their jobs, making countless phone calls [to people] who kept saying they did not want to speak with her. I was talking to one of my friends, who had just recently gotten over a drug addiction, who she tried to talk to about this case. He told me it was really painful for him, and he didn’t want to go back and revisit this crap.

There are two sides to every story (at least). From Koenig throughout the podcast, we get the persistent reporter angle—knocking on doors, trying to get the full story, leaving no stone unturned. From Jay we hear what that looked like to some on the other side of those doors—harassment at work, disregard for their decisions not to speak to her, and reminders of painful memories.

Which brings us to Hae’s family. Here is what Koenig has to say about Hae’s family in Episode 9, “To Be Suspected:”

For many, many months we tried to contact Hae’s family, to tell them we were doing this story, and in hopes that they might want to talk to us about Hae . In my twenty plus years of reporting, I have never tried harder to find anyone. Letters, in English and in Korean, phone calls, social media, friends of friends of friends, two private detectives, Korean-speaking researchers, people knocking on doors in three different states, calls to South Korea. We never heard back from them. I learned a few days ago that they know what we’re doing; my best guess is that they want no part of it, which I respect.

I struggle with this, as other critics have. To me, respecting Hae’s family doesn’t end with calling off the search party. Their silence should tell you something about the possibility that they might not want this, to dredge up the pain of their daughter’s murder as a “whodunnit” radio show. This podcast has become a sensation. If Hae’s family did not want to be contacted in the first place, what do you think has happened since? At best, they have successfully ignored the show itself but by thinking about it have unveiled the pain and suffering from which they had spent fifteen years trying to heal. At worst, armchair detectives like those on Reddit who found Jay’s home have found Hae’s family and jeopardized not only their peace of mind but also their safety.

If Koenig truly was mindful “all the time” that the people in her story are real people, as she says to Jay in her emailed statement, I think Hae’s family not wanting to be contacted should have given her more pause.

A user claiming to be Hae’s brother posted the following on Reddit:

TO ME ITS REAL LIFE. To you listeners, its another murder mystery, crime drama, another episode of CSI. You weren’t there to see your mom crying every night, having a heartattck when she got the new that the body was found, and going to court almost everyday for a year seeing your mom weeping,crying and fainting. You don’t know what we went through. Especially to those who are demanding our family response and having a meetup… you guys are disgusting. SHame on you. I pray that you don’t have to go through what we went through and have your story blasted to 5mil listeners.

There was verification from the Reddit moderators, though the evidence was removed as it was a Facebook chat sent from Koenig and producer Dana Chivvis that revealed their personal profiles. But whether or not this message is legitimately from Hae’s brother doesn’t really matter. What matters is that this could be exactly what Hae’s family members are going through because of Serial.

After finishing the series, I started reading all the backlash and the defense of the backlash, and I opened the floodgates. There are other criticisms that I hadn’t given much thought to previously, some of which I disagree with, and others which I find valid. Many have discussed Koenig’s treatment of Hae as problematic, as she embodies the trope of “the dead woman” often seen in crime fiction. Or that she becomes “sidelined” and “her death becomes entertainment,” all while Koenig evades the conversation of domestic violence and the fact that “charming” men (and people) are common perpetrators of violence against women.

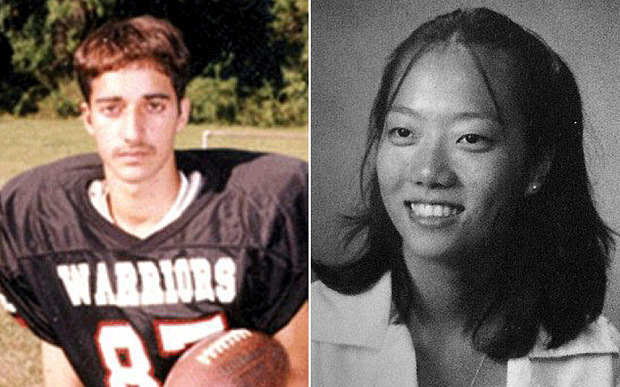

Adnan Syed and Hae Min Lee

Source: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/men/the-filter/11303390/Its-time-to-tell-it-like-it-is-the-Serial-podcast-was-rubbish.html

Others have pointed to Koenig’s own white privilege, or the treatment of Hae and Adnan as the “model minorit[ies]” while Jay gets cast as the “thuggish” / “threatening and untrustworthy black man.” Others have asked whether listeners up in arms about Adnan’s possibly wrongful conviction “want to grapple with the larger issues of the US criminal justice system” or whether they just care about this one case.

Most of the criticism and my own delayed disapproval come down to one thing: Koenig’s treatment of the story as if it were fictional entertainment. Under that umbrella come the more specific problems, but that’s what it all boils down to.

And that’s why I enjoyed Serial for the first 11 episodes up until her flippant and callous response to Adnan’s letter. I was entertained. It was compelling. I liked listening to the story and getting caught up in it. I don’t blame any listener for that. But I do blame Koenig for letting it happen, for allowing us to forget the real human lives that “her story” upturned. Because even though her story is over, the effect of it is irreversible on the lives of those involved.

I’ll close with a quote from Rabia Chaudry, the very person that brought the case to Koenig in the first place. This is from Rabia’s blog, and I’d argue that though she says “those who know and love Adnan,” she could be talking about any of the real people involved in the case, whether they believe Adnan to be guilty or innocent:

“I don’t deny I am relieved that Serial is over…But because as difficult as it was for the general public to swing back and forth between sides, guided effortlessly by Sarah, it was even harder on those who know and love Adnan.

We never knew what parts of the story Sarah would chose to tell, and how she would chose to tell it. And I promise you, the parts you tell and how you tell it make all the difference in what the world hears. So we would wait to see which way the wind blew each week, and often wonder why Sarah left out certain things. In a way, as Sarah wondered if Adnan was manipulating her, we all wondered if Sarah was doing the same thing to us.”

And she will be. Next time. Second season of Serial.